|

Dizgi Ana Hatları

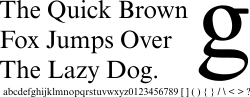

Dizginin ne olduğunu ve nasıl yapıldığını anlamak için öncelikle tipografik terminolojiyi bilmek gerekir. Tipografik terminoloji dizgide ele alınan belli başlı tüm öğelerin açıklamalarını içerir.

Page

Pagination

Pagination is the system by which the information on a newspaper, bookpage, manuscript, or otherwise handwritten, printed or displayed document is laid out.

In a strict sense of the word, it can mean the consecutive numbering to indicate the proper order of the pages, which was rarely found in documents pre-dating 1500, and only became common practice circa 1550, when it replaced foliation, which numbered only the front sides of folios.

Pagination can also refer to the process of organizing information on web pages. For instance, threads on a bulletin board might be paginated such that 50 appear on each page.

Recto and verso

The recto is the right-hand page and the verso the left-hand page of a folded sheet or bound item, such as a book, broadsheet, or pamphlet. These are terms of art in the binding, printing, and publishing industries, and can be applied more broadly to any field where physical documents are exchanged.

The term recto-verso describes two-sided text. The terms are important in the field of codicology, where each physical sheet of a manuscript is numbered and the sides are referred to as recto and verso. Critical editions of manuscripts will often mark the position of text in the original manuscript, or manuscripts, in the style '42r.' or '673vº'.

The terms are carried over into printing, recto-verso is the norm for printed books, but was an important advantage of the printing-press over the much older Asian woodblock printing method, which printed by rubbing from behind the page being printed, and so could only print on one side of a piece of paper.

The distinction between recto and verso can be convenient in the annotation of scholarly books, particularly in bilingual edition translations.

The "recto" and "verso" terms can also be employed for the front and back of a one-sheet artwork, particularly in drawing. A recto-verso drawing is a sheet with drawings on both sides, for example in a sketchbookalthough usually in these cases there is no obvious primary side. Some works are planned to exploit being on two sides of the same piece of paper, but usually the works are not intended to be considered together. Paper was relatively expensive in the past; indeed good drawing paper still is much more expensive than normal paper.

By book publishing convention, the first page of a book, and of sometimes of each section and chapter of a book, is a recto page,[1] and hence all recto pages will have odd numbers and all verso pages will have even numbers.[2][3]

Margin

In typography, a margin is the space that surrounds the content of a page. The margin helps to define where a line of text begins and ends. When a page is justified the text is spread out to be flush with the left and right margins. When two pages of content are combined next to each other (known as a two-page spread), the space between the two pages is known as the gutter.

The standard margin in most word processing programs is 1 inch for Letter paper and 2.5 cm for A4 paper, with 2.0 cm for the bottom margin in one-page layout or for the inner margin in two-page spread.

Column

In typography, a column is one or more vertical blocks of content positioned on a page, separated by margins and/or rules. Columns are most commonly used to break up large bodies of text that cannot fit in a single block of text on a page. Additionally, columns are used to improve page composition and readability. Newspapers very frequently use complex multi-column layouts to break up different stories and longer bodies of texts within a story. Column can also more generally refer to the vertical delineations created by a typographic grid system which type and image may be positioned.

For best legibility, typographic manuals suggest that columns should contain roughly 60 characters per line.[1] One formula suggests multiplying the point size of the font by 2 to reach how wide a column should be in picas[2] in effect a column width of 24 ems. Following these guidelines usually results in multiple narrow columns being favored over a single wide column.[3] Historically, books containing predominantly text generally have around 40 lines per column. However, this rule of thumb does not apply to more complex text that contain multiple images or illustrations, footnotes, running heads, folios, and captions.[4]

Column contrast refers to the overall color or greyness established by the column, and can be adjusted in a number of ways. One way is to adjust the relationship between the width and height of the column. Another way is to make adjustments to the typeface, from choosing a specific font, to adjusting weight, style, size and leading. Column contrast can be used to establish hierarchy, to balance the page composition, and to visually activate ares of the page.[5]

Canons of page construction

The canons of page construction are a set of principles in the field of book design used to describe the ways that page proportions, margins and type areas (print spaces) of books are constructed.

The notion of canons, or laws of form, of book page construction was popularized by Jan Tschichold in the mid to late twentieth century, based on the work of J. A. van de Graaf, Raúl M. Rosarivo, Hans Kayser, and others.[1] Tschichold wrote: Though largely forgotten today, methods and rules upon which it is impossible to improve have been developed for centuries. To produce perfect books these rules have to be brought to life and applied.[2] Kayser's 1946 Ein harmonikaler Teilungskanon[3] had earlier used the term canon in this context.

Typographers and book designers apply these principles to this day, with variations related to the availability of standardized paper sizes, and the diverse types of commercially printed books.[4]

Pull quote

A pull quote (also known as a lift-out quote or a call-out) is a quotation or edited excerpt from an article that is placed in a larger typeface on the same page, serving to lead readers into an article and to highlight a key topic. The term is principally used in journalism and publishing. Some publications choose not to align the pull quote with the columns on a page; in that case, it cuts into two or more columns to reduce the linearity of a page. Placement of a pull quote on a page is usually defined in a publication's own style manual.

Paragraf

In typesetting, a widow is the final line of a paragraph if it falls at the top of the following page [or column] of text, separated from the remainder of the paragraph on the previous page [or column]. A related term, orphan, refers to the first line of a paragraph if it appears on its own at the bottom of a page [or column] with the remaining portion of the paragraph appearing on the following page [or column];[1] in other words the first line of the paragraph has been "left behind" by the remaining portion of text.

In simpler terms, a widow is generally a single line of a paragraph appearing at the top of a page and an orphan is generally a single line of a paragraph appearing at the bottom of a page.

A common mnemonic is that "an orphan has no past; a widow has no future".[2]

Another way is to think of orphans as generally being younger than widows; thus, orphaned lines happen first, at the start of paragraphs (affecting and stranding the first line), and widowed lines happen last, at the end of paragraphs (affecting and stranding the last line). Orphaned lines appear at the "birth" (start) of paragraphs; widowed lines appear at the "death" (end) of paragraphs.

Writing guides generally suggest that a manuscript should have no widows and orphans[3][citation needed] even when avoiding them results in additional space at the bottom of a page or column. Some techniques for eliminating widows include:

- Forcing a page break early, producing a shorter page;

- Adjusting the leading, the space between lines of text (although such carding or feathering is usually frowned upon);

- Adjusting the spacing between words to produce 'tighter' or 'looser' paragraphs;

- Adjusting the hyphenation of words within the paragraph;

- Adjusting the page's margins;

- Subtle scaling of the page, though too much non-uniform scaling can visibly distort the letters;

- Rewriting a portion of the paragraph;

- Reduce the tracking of the words;

- Adding a pull quote to the text (more common for magazines); and

- Adding a figure to the text, or resizing an existing figure.

An orphan is cured more easily, by inserting a blank line or forcing a page break to push the orphan line onto the next page to be with the rest of its paragraph. Such a cure may have to be undone if editing the text repositions the automatic page/column break.

Most full-featured word processors and page layout applications include a paragraph setting (or option) to automatically prevent widows and orphans. When the option is turned on, an orphan is forced to the top of the next page or column; and the line preceding a widow is forced to the next page or column with the last line. This automatic adjustment to a page's layout can be a source of frustration for someone who is unaware of why text is shifted from one page to the next.

Leading

In typography, leading (pronounced /'l?d??/, rhymes with heading) refers to the amount of added vertical spacing between lines of type. In consumer-oriented word processing software, this concept is usually referred to as "line spacing". Leading may sometimes be confused with tracking, which refers to the horizontal spacing between letters or characters.

The word comes from lead strips that were put between set lines. When type was set by hand in printing presses, slugs or strips of lead (reglets) of appropriate thicknesses were inserted between lines of type to add vertical space, to fill available space on the page.

Text set "solid" (no leading) appears cramped, with ascenders almost touching descenders from the previous line. The lack of white space between lines makes it difficult for the eye to track from one line to the next, and hampers readability.

River

In typography, rivers, or rivers of white, are visually unattractive gaps appearing to run down a paragraph of text. They can occur with any spacing, though they are most noticeable with wide interword spaces caused by either full text justification or monospaced fonts.

A less-frequently-used term is a lake, which refers to a cluster of adjacent or intertwined rivers that create a lighter area in the midst of a block of type.

Typographic alignment

In typesetting and page layout, alignment or range, is the setting of text flow or image placement relative to a page, column (measure), table cell or tab. The type alignment setting is sometimes referred to as text alignment, text justification or type justification.

Justification

In typesetting, justification (can also be referred to as 'full justification') is the typographic alignment setting of text or images within a column or "measure" to align along both the left and right margin. Text set this way is said to be "justified".

In justified text, the spaces between words, and, to a lesser extent, between glyphs or letters (kerning), are stretched or sometimes compressed in order to make the text align with both the left and right margins. When using justification, it is customary to treat the last line of a paragraph separately by left or right aligning it, depending on the language direction. Lines in which the spaces have been stretched beyond their normal width are called loose lines, while those whose spaces have been compressed are called tight lines.

The following table displays the difference between a justified (flush left and flush right) and a flush left (and ragged right) text.

Karakter

Ligature

In writing and typography, a ligature occurs where two or more graphemes are joined as a single glyph. Ligatures usually replace consecutive characters sharing common components, and are part of a more general class of glyphs called "contextual forms" where the specific shape of a letter depends on context such as surrounding letters or proximity to the end of a line.

Tarihi

At the origin of typographical ligatures is the simple running together of letters in manuscripts. Already the earliest known script, Sumerian cuneiform, includes many cases of character combinations that over the script's history gradually evolve from a ligature into an independent character in its own right. Ligatures figure prominently in many historical scripts, notably the Brahmic abugidas, or the bind rune in Migration Period Germanic inscriptions.

Medieval scribes, writing in Latin, conserved space and increased writing speed by combining characters and by introduction of scribal abbreviation. For example, in blackletter, letters with right-facing bowls (b, o, and p) and those with left-facing bowls (c, e, o, and q) were written with the facing edges of the bowls superimposed. In many script forms characters such as h, m, and n had their vertical strokes superimposed. Scribes also used scribal abbreviations to avoid having to write a whole character at a stroke. Manuscripts in the fourteenth century employed hundreds of such abbreviations.

In hand writing, a ligature is made by joining two or more characters in a way they wouldn't usually be, either by merging their parts, writing one above another or one inside another; while in printing, a ligature is a group of characters that is typeset as a unit, and the characters don't have to be joined - for example, in some cases fi ligature prints letters f and i more separated than when they are typeset as separate letters.

When printing with movable type was invented around 1450,[1] typefaces included many ligatures. However they began to fall out of use with the advent of the wide use of sans serif machine-set body text in the 1950s and the development of inexpensive phototypesetting machines in the 1970s, which did not require journeyman knowledge or training to operate. One of the first computer typesetting programs to take advantage of computer driven typesetting (and later laser printers) was the TeX program of Donald Knuth (see below for more on this). This trend was further strengthened by the desktop publishing revolution around 1985. Early computer software in particular (except for TeX) had no way to allow for ligature substitution (the automatic use of ligatures where appropriate), and in any case most new digital fonts did not include any ligatures. As most of the early PC development was designed for and in the English language, which already saw ligatures as optional at best, a need for ligatures was not seen. Ligature use fell as the number of employed, traditionally-trained hand compositors and hot metal typesetting machine operators dropped.

With the increased support for other languages and alphabets in modern computing, and the resulting improved digital typesetting techniques such as OpenType, ligatures are slowly coming back in use.

Latin alphabet

[edit] Stylistic ligatures

Many ligatures combine f with an adjacent letter. The most prominent example is ? (or fi, rendered with two normal letters). The dot above the i in many typefaces collides with the hood of the f when placed beside each other in a word, and are combined into a single glyph with the dot absorbed into the f. Other ligatures with the letter f includes fj,[2] fl (?), ff (?), ffi (?), ffl (?), and specific Slovak ligature fl (and in theory also ffl, fl, ffl). Ligatures for fa, fe, fo, fr, fs, ft, fb, fh, fu, fy, and for f followed by a full stop, comma, or hyphen, as well as the equivalent set for the doubled ff and fft are also used, though are less common.

Sometimes, a ligature crossing the boundary of a composite word (e.g., ff in shelfful[3]) is considered undesirable, and computer programs (such as TeX) provide a means of suppressing ligatures.

Some fonts include an fff ligature (the Requiem Italic font by Jonathan Hoefler contains even an fffl ligature), intended for German compound words like Sauerstoffflasche ("oxygen tank") and Schifffahrt ("boat trip") (the latter word is only written with fff if the writer follows the spelling reform of 1996). Official German orthography as outlined in the Duden however prohibits ligatures across composition boundaries, and since the sequence fff in German only ever occurs across such boundaries (Schiff-fahrt, Sauerstoff-flasche), these ligatures cannot be correctly employed for German.[4]

Turkish has a dotted and dotless "I", with next to each other words like fırın ("oven") and fikir ("idea"). The fi ligature would obscure the distinction and is therefore not used in Turkish typography, and neither are other ligatures like that for fl, which correspond to rare letter combinations anyway.

"ß" in the form of a "?z" ligature on a street sign in Berlin ("Petersburger Straße"). The sign on the right ("Bersarinplatz") ends with a "tz"-ligature.

A remnant of a tz ligature from Fraktur, a family of German blackletter typefaces, originally mandatory in Fraktur but now only employed stylistically, can be seen to this day on street signs for city squares whose name contains Platz or ends in -platz.

Sometimes ligatures for st (?), ?t (?), ch, ct, and Qu are used (e.g. in the typeface Linux Libertine).

Harf Aralığı

In typography, letter-spacing, also called tracking, refers to the amount of space between a group of letters to affect density in a line or block of text. Since the advent of personal computers the term tracking is frequently used. In professional typography and graphic design the term letter-spacing is more commonly used.

Letter-spacing/tracking can be confused with kerning. Letter-spacing refers to the overall spacing of a word or block of text affecting its overall density and texture. Kerning is a term applied specifically to the adjustment of spacing of two particular characters to correct visually uneven spacing.

Letter-spacing adjustments are frequently used in news design. The speed with which pages must be built on deadline does not usually leave time to rewrite paragraphs that end in split words or that create orphans or widows. Letter-spacing is increased or decreased by modest (usually unnoticeable) amounts to fix these unattractive situations.

Kerning

In typography, kerningless commonly, mortising (referring to the process of physically removing material from the cast character)is the process of adjusting letter spacing in a proportional font. In a well-kerned font, the two-dimensional blank spaces between each pair of letters all have similar area.

Capital letter (Majüskül)

Capital letters or majuscules [IPA pronunciation: /m?'d??skjuls, 'mæd???skjuls/], in the Roman alphabet A, B, C, D, etc., may also be called capitals, or caps. Upper case, upper-case, or uppercase is also often used in this context as synonym of capital. Manual typesetters kept them in the upper drawers of a desk or in the upper type case, while keeping the more frequently used minuscule letters in the lower type case. This practice might date back to Johannes Gutenberg.

Capital and small letters are differentiated in the Roman, Greek, Glagolitic, Cyrillic and Armenian alphabets. Most writing systems (such as those used in Georgian, Arabic, Hebrew, and Devanagari) make no distinction between capital and lowercase letters (and, of course, logographic writing systems such as Chinese have no "letters" at all). Indeed, even European languages did not make this distinction before about 1300; both majuscule and minuscule letters existed, but a given text would use either one or the other.

Lower case (Minüskül)

Lower case (also lower-case or lowercase), minuscule, or small letters are the smaller form of letters, as opposed to upper case or capital letters, as used in European alphabets (Greek, Latin, Cyrillic, and Armenian). For example, the letter "a" is lower case while the letter "A" is upper case.

Originally alphabets were written entirely in capital letters, spaced between well-defined upper and lower bounds[citation needed]. When written quickly with a pen, these tended to turn into rounder and much simpler forms, like uncials[citation needed]. It is from these that the first minuscule hands developed, the half-uncials and cursive minuscule, which no longer stay bound between a pair of lines.

These in turn formed the foundations for the Carolingian minuscule script, developed by Alcuin for use in the court of Charlemagne, which quickly spread across Europe. Here for the first time it became common to mix both upper and lower case letters in a single text.

The term "lower case" comes from manual typesetting. Since minuscules were more frequent in text than majuscules, typesetters placed them in the lower and nearer type case, while the case with the majuscules (the "upper case") was above and behind, a longer reach.

The word minuscule is often spelled miniscule, by association with the unrelated word miniature and the prefix mini-. This has traditionally been regarded as a spelling mistake (since minuscule is derived from the word minus[1]), but is now so common that some dictionaries tend to accept it as a nonstandard or variant spelling.[2] However, miniscule is still less likely to be used for lower-case letters.

Small caps

In typography, small capitals (usually abbreviated small caps) are uppercase (capital) characters set at the same height as surrounding lowercase (small) letters or text figures. They are used in running text to prevent capitalized words from appearing too large on the page, and as a method of emphasis or distinctiveness for text alongside or instead of italics, or when boldface is inappropriate. For example, they can be used to draw attention to the opening phrase or line of a new section of text, or to provide an additional style in a dictionary entry where many parts must be typographically differentiated.

Typically, the height of a small capital will be one ex, the same height as most lowercase characters in the font; classically, small caps were very slightly taller than x-height.[citation needed] Well-designed small capitals are not simply scaled-down versions of normal capitals; they normally retain the same stroke weight as other letters, and a wider aspect ratio to facilitate readability.

Many word processors and text formatting systems include an option to format text in caps and small caps; this leaves uppercase letters as they are but converts lowercase letters to small caps. How this is implemented depends on the typesetting system; some can use true small caps associated with a font, making text such as "Latvia joined NATO on March 29, 2004" look proportional, but most modern digital fonts do not have a small-caps case, so the typesetting system simply reduces the uppercase letters by a fraction, making them look out of proportion. (Often,[citation needed] in text, the next bolder version of the small caps generated by such systems will match well with the normal weights of capitals and lower case, especially when such small caps are extended about 5% or letterspaced a half point or a point.)

Initial

In a written work, an initial is a letter at the beginning of a work, a chapter or a paragraph that is larger than the rest of the text. The word comes from the Latin initialis, which means standing at the beginning. It is often several lines in height and in older books or manuscripts sometimes ornately decorated.

In illuminated manuscripts, initials with images inside them, like those illustrated here, are known as historiated initials; they were an invention of the Insular art of the British Isles in the 8th century. Initials containing, typically, plant-form spirals with small figures of animals or men that do not represent a specific person or scene are known as "inhabited" initials. Certain important initials, such as the B of Beatus vir ... at the opening of Psalm 1 at the start of a vulgate Latin psalter, could occupy a whole page of a manuscript.

These specific initials, in an illuminated manuscript, were also called Initiums.

Font

Serif

In typography, serifs are semi-structural details on the ends of some of the strokes that make up letters and symbols. A typeface that has serifs is called a serif typeface (or seriffed typeface). A typeface without serifs is called sans-serif, from the French sans, meaning without. Some typography sources refer to sans-serif typefaces as "grotesque" (in German "grotesk") or "Gothic," and serif types as "Roman."

Usage

In traditional printing serifed fonts are used for body text because they are considered easier to read than sans-serif fonts for this purpose.[1] Sans-serif fonts are more often used in headlines, headings, and shorter pieces of text and subject matter requiring a more casual feel than the formal look of serifed types.

Serifed fonts are the overwhelming typeface choice for lengthy text printed in books, newspapers and magazines.[2] For such purposes sans serif fonts are more acceptable in Europe than in North America, but still less common than serifed typefaces.

While in print serifed fonts are considered more readable, sans-serif is considered more legible on computer screens.[citation needed] For this reason the majority of web pages employ sans-serif type.[3] Hinting information, anti-aliasing and subpixel rendering technologies have partially mitigated the legibility problem of serif fonts on screen. But the basic constraint of screen resolution typically 100 pixels per inch or less and small font sizes continues to limit their readability on screen.

As serifs originated in inscription, they are generally not utilized in handwriting. A common exception is the printed capital I, where the addition of serifs distinguishes the character from lowercase L. Printed capital Js, and the numeral 1 are also often handwritten with serifs

.

Serif fonts can be broadly classified into one of four subgroups: old style, transitional, slab serif, or modern.

The Adobe Garamond typeface, an example of an old-style serif

[edit] Old Style

Old style or humanist typefaces date back to 1465, and are characterized by a diagonal stress (the thinnest parts of letters are at an angle rather than at the top and bottom), subtle differences between thick and thin lines (low line contrast), and excellent readability. Old style typefaces are reminiscent of the humanist calligraphy from which their forms were derived.

It has been said[weasel words] that the angled stressing of old style faces generates diagonal lock, which, when combined with their bracket serifs creates detailed, positive word-pictures (see bouma) for ease of reading. However, this theory is mostly contradicted by the parallel letterwise recognition model, which is widely accepted by cognitive psychologists who study reading.[citation needed]

Old style faces are sub-divided into Venetian and Aldine or Garalde. Examples of old style typefaces include Adobe Jenson (Venetian), Janson, Garamond, Bembo, Goudy Old Style, and Palatino (all Aldine or Garalde).

The Times New Roman typeface, an example of a transitional serif

[edit] Transitional

Transitional or baroque serif typefaces first appeared in the mid-18th century. They are among the most common, including such widespread typefaces as Times New Roman (1932) and Baskerville (1757). They are in between modern and old style, thus the name "transitional." Differences between thick and thin lines are more pronounced than they are in old style, but they are still less dramatic than they are in modern serif fonts.

The Bodoni typeface, an example of a modern serif

[edit] Modern

Modern or Didone serif typefaces, which first emerged in the late 18th century, are characterized by extreme contrast between thick and thin lines. Modern typefaces have a vertical stress, long and fine serifs, with minimal brackets. Serifs tend to be very thin and vertical lines are very heavy. Most modern fonts are less readable than transitional or old style serif typefaces. Common examples include Bodoni, Didot, Century Schoolbook and Computer Modern.

Sans-serif

In typography, a sans-serif or sans serif typeface is one that does not have the small features called "serifs" at the end of strokes. The term comes from the French word sans, meaning "without".

In print, sans-serif fonts are more typically used for headlines than for body text.[1] The conventional wisdom is serifs help guide the eye along the lines in large blocks of text. Sans-serifs, however, have acquired considerable acceptance for body text in Europe.

Sans-serif fonts have become the de facto standard for body text on-screen, especially online. This is partly because interlaced displays may show twittering on the fine details of the horizontal serifs. However, the resolution of digital displays in general can make fine details like serifs disappear or appear too large.

Before the term sans-serif became standard in English typography, a number of other terms had been used. One of these outmoded terms for sans serif was gothic, which is still used in East Asian typography and sometimes seen in font names like Century Gothic.

Sans-serif fonts are sometimes, especially in older documents, used as a device for emphasis, due to their typically blacker type color.

Italic type

In typography, italic type (pronounced [??'tæl?k] or [a?'tæl?k]) refers to cursive typefaces based on a stylized form of calligraphic handwriting. The influence from calligraphy can be seen in their usual slight slanting to the right. Different glyph shapes from roman type are also usually usedanother influence from calligraphy.

This style is called "italic" simply because the style originated in Italy.

It is distinct therefore from oblique type, in which the font is merely distorted into a slanted orientation. However uppercase letters are often oblique type or swash capitals rather than true italics.

Oblique type

Oblique type (or slanted, sloped) is a form of type that slants slightly to the right, used in the same manner as italic type. Unlike italic type, however, it does not use different glyph shapes; it uses the same glyphs as roman type, except distorted. Oblique fonts are usually associated with sans-serif typefaces, especially with geometric faces, as opposed to humanist ones whose design tends to draw more on history. Oblique and italic type are often confused by non-designers.

The start of this confusion possibly appeared when Adrian Frutiger named the slanted versions of his typefaces Univers and Frutiger as italic. Following this viewpoint, sans-serif typefaces often do not have true italic versions. The Gill Sans and Goudy Sans typefaces are two well-known exceptions. The sans-serif fonts within the ClearType Font Collection introduced in Windows Vista typefaces have true italic versions, as does the older Trebuchet MS typeface.

True oblique typefaces have letterforms which are slanted, but maintain the proportions of counters and the thick-and-thin quality of strokes. Mechanically or optically-skewed oblique fonts are considered inferior, and unfit for most professional typography and graphic design. They are however sometimes generated automatically by computer display systems when italic style is requested but appropriate font data is absent.

Emphasis (typography)

In typography, emphasis is the exaggeration of words in a text with a font in a different style from the rest of the textto emphasize them.

Methods & use of emphasis

The human eye is very receptive to differences in brightness within a text body. One can therefore differentiate between types of emphasis according to whether the emphasis changes the blackness of text.

A means of emphasis that does not have much effect on blackness is the use of italics, where the text is written in a script style, or the use of oblique, where the vertical orientation of all letters is slanted to the left or right. With one or the other of these techniques (usually only one is available for any typeface), words can be highlighted without making them stand out much from the rest of the text (inconspicuous stressing). Traditionally, this is used for marking passages that have a different context, such as words from foreign languages, book titles, and the like.

By contrast, boldface makes text darker than the surrounding text. With this technique, the emphasized text strongly stands out from the rest; it should therefore be used to highlight certain keywords that are important to the subject of the text, for easy visual scanning of text. For example, printed dictionaries often use boldface for their keywords, and the names of articles can conventionally be marked in bold.

If the text body is typeset in a serif typeface, it is also possible to highlight words by setting them in a sans serif face; this practice is somewhat archaic.

Small capitals are also used for emphasis, especially for the first line of a section, sometimes accompanied by or instead of a drop cap.

In Cyrillic and blackletter typography, it used to be common to emphasize words using letterspaced type. This practice for Cyrillic has become obsolete with the availability of Cyrillic italic and small capital fonts (Bringhurst version 3.0, p 32).

The above-mentioned methods of emphasis fall under the general technique of emphasis through a change of font

Noktalama

Punctuation is everything in written language other than the actual letters or numbers, including punctuation marks (listed at right), inter-word spaces and indentation.[1]

Punctuation marks are symbols that correspond to neither phonemes (sounds) of a language nor to lexemes (words and phrases), but which serve to indicate the structure and organization of writing, as well as intonation and pauses to be observed when reading it aloud. See orthography.

In English, punctuation is vital to disambiguate the meaning of sentences. For example, "woman, without her man, is nothing," and "woman: without her, man is nothing," have greatly different meanings, as do "eats shoots and leaves" and "eats, shoots and leaves."[2]

The rules of punctuation vary with language, location, register and time, and are constantly evolving. Certain aspects of punctuation are stylistic and are thus the author's (or editor's) choice. Tachygraphic language forms, such as those used in online chat and text messages, may have wildly different rules.

Hyphenation

The hyphen ( - ) is a punctuation mark. It is used both to join words and also to separate syllables of a single word. It is often confused with dashes ( , , ? ), which are longer and have different uses, and with the minus sign ( - ) which is also longer. (When typing, some writers use two consecutive hyphens to represent a dash for speed or if a proper dash character is not available.) The use of hyphens is called hyphenation.

|

![]()